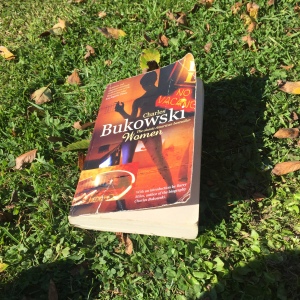

Women depicts Bukowski’s later life as a writer through his roman-à-clef character, Henry Chinaski or ‘Hank’, and acts as a sequel to his celebrated work, Post Office.

No surprise Hank is also a writer whose name alone manages to draws big crowds to readings of salacious poetry and literature. You don’t learn an awful lot about the content of his writing but are given a pretty good idea that Hank’s work is ultimately a reflection of his alcoholic and licentious lifestyle, which Bukowski portrays throughout the book only too well.

When asked by an aspiring writer: “You talk about drinking a lot in your books. Do you think drinking has helped your writing” Hank merely replies “No. I’m just an alcoholic who became a writer so that I would be able to stay in bed until noon.”

Hank manages to earn enough to pay the rent and to keep himself tanked up on booze five or six nights a week. Amidst drinking himself to near oblivion his second favourite thing is sex, and due to the nature of his albeit passable celebrity status, he seems to find no problem whatsoever in intriguing women of easy virtue.

Many would label Hank a misogynist and you couldn’t really blame them… Bukowski doesn’t hold back with raw and gritty descriptions and the ‘C’ word quickly becomes commonplace. But Hank doesn’t appear to hate or hold prejudices against women, he simply enjoys a high frequency of casual affairs and in his defence everything about his character and disposition screams the fact he has no interest in settling down –

When Hank’s attempts to chase a woman of sophistication fall short he candidly deduces:

‘Katherine knew there was something about me that wasn’t wholesome in the sense of wholesome is as wholesome does. I was drawn to all the wrong things: I liked to drink, I was lazy, I didn’t have a god, politics, ideas, ideals. I was settled into nothingness’

The sooner you accept Bukowski’s approach the more at peace you can be with his characters. American low-life unapologetically describes the lives of less reputable members of society, which may sound trivial but storytelling that focuses on a combination of poverty, promiscuity or criminality seldom succeed in the mainstream.

With exception to the latter – portrayals of organised crime have always captivated audiences but this is different. They are typically coupled with a rags to riches narrative apparent in the reportedly inaccurate glamourisation of the Italian/American mafia.

Tony Soprano, the archetype antihero, is a criminal and womaniser but he is rich and powerful, which is why to many he remains aspirational. On the other hand similarly aged Hank still lives in a rough part of town and few would aspire to his uncertain and unconventional position of living from one day to the next, which to me is what makes Bukowski’s ‘in the moment’ style so readable.