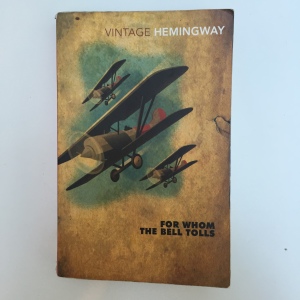

Hemingway is commonly referred to as a minimalist and A Farewell to Arms with its simple forms and structure may well be one of the works which best exemplifies this. In this vein I’ll be true to form and keep this short and sweet!

Frederic Henry is an American who joins the ambulance corps in the Italian Army during World War One, something Hemingway himself did at the age of eighteen, and although this clearly qualifies as roman-à-clef (a novel in which real people or events appear with invented names) I was surprised to find how much the story still differs from his own experiences.

Frederic or ‘Tenete’, an alias given to him by his Italian colleagues, meets an English girl early on and despite taking an interest it’s not until she nurses him in hospital that he develops deeper feelings for her.

Tenete is a likeable chap and has a nonchalant disposition characterised by his enjoyment in going to the track, his commentary on war news and his taste for alcohol – the last of which leads to a somewhat premature exit from the hospital ward! As with many of Hemingway’s characters Tenete doesn’t seem to overthink anything and even in tense situations where you’d expect a degree of fear or anxiety there is none.

If anything is testament to Hemingway’s minimalism, it’s his brief encounters with emotion or arguably his avoidance of it altogether. It’s most probably unintentional, but personally I think the distinct lack of emotion in certain instances can prompt the reader to think harder about a situation and consequently feel it more intensely.

The following passage comes from a rare moment of introspection:

If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

No one would doubt that bravery was clearly one of Hemingway’s qualities and it must be said that Tenete’s assuredness in testing situations and unemotional mindset may simply be an embodiment of how Hemingway himself thought.

How accurate a conclusion that is, we’ll never know, but he clearly had no aspiration to live a quiet life and his courageous attitude must still provide inspiration to journalists, aid workers or anyone looking for an adventure.

Regardless of Hemingway’s neutral style A Farewell to Arms is an accessible and enjoyable wartime account, free of sensationalism or nationalistic agendas.